Modern Self Café v2: Kant Goethe There

Posted: December 23, 2024 Filed under: AI-Powered Essays | Tags: models, modernity, philosophy, truth 1 CommentContinued from Modern Self Café: Galileo, Descartes, Mersenne

ChatGPT Prompt

Imagine a similar group set in the time of Kant.

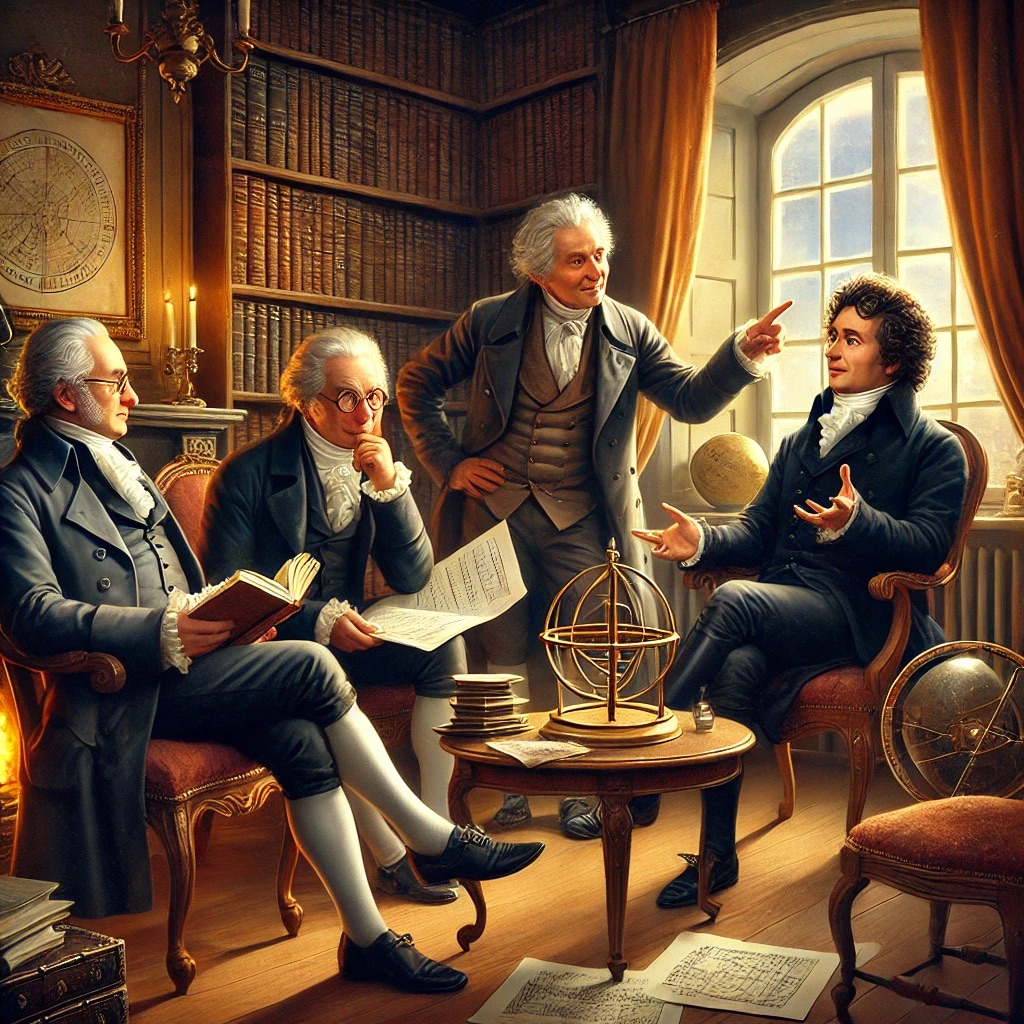

Setting: A cozy salon in Königsberg in the late 18th century. The conversation revolves around the Enlightenment’s intellectual revolution and the transition from Newtonian mechanics and rationalism to Immanuel Kant‘s transcendental idealism. The group includes Kant, Leonhard Euler, Joseph-Louis Lagrange, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. They discuss how their respective disciplines—philosophy, mathematics, physics, and natural science—are reshaping humanity’s understanding of reality.

Kant: Gentlemen, it strikes me that we are at a crossroads, much like Galileo and Descartes before us. They sought to uncover the laws of nature through reason and observation. But now we must ask: what are the limits of reason itself?

Euler: (adjusting his spectacles) And yet, Herr Kant, mathematics has no such limits. In the clarity of numbers and equations, we uncover universal truths. Surely, these are the purest expressions of reason, untouched by the senses or subjective experience.

Kant: *Ah, Herr Euler, but is mathematics not constructed by the mind itself? I argue in my *Critique of Pure Reason* that space and time are forms of intuition, frameworks through which the mind organizes its experiences. Without these, mathematics could not exist.*

Lagrange: (leaning forward) And yet, Professor Kant, mathematics extends beyond mere intuition. Take my work in mechanics: the principles I have laid out in my Analytical Mechanics describe motion in terms of energy and equilibrium, independent of time or space as we perceive them. These laws must hold in any conceivable universe.

Kant: Indeed, your formulations are elegant, Herr Lagrange, but they still rely on the mind’s innate categories—causality, for instance. Newton himself assumed these categories without questioning their origin. My philosophy seeks to reveal that these “universal laws” are the conditions under which we can perceive anything at all.

Goethe: (smiling) Kant, you philosophers are so fascinated by abstractions, you forget the richness of nature itself. My work in Theory of Colors has shown that perception is not merely a passive reception of light. The mind and nature collaborate in a dance of experience. Can we truly separate the observer from the observed?

Euler: (chuckling) A poet among mathematicians! Herr Goethe, while your observations of light are intriguing, they cannot rival Newton’s optics. His work laid the foundation for the modern understanding of light as particles, governed by immutable laws.

Goethe: (with a hint of defiance) Immutable laws? Or merely convenient approximations? Newton’s experiments fragmented light into its parts, but he missed its unity. My approach considers the whole, the interplay between light and shadow, color and perception. Nature resists the simplifications of mathematics.

Lagrange: Still, Goethe, we cannot dismiss mathematics as mere simplification. Consider the predictive power of equations—how they unify phenomena under a single framework. My equations of motion have guided the design of machines, the orbits of planets. Is this not a testament to the universality of mathematics?

Kant: (raising a hand) Gentlemen, you are both correct, yet both miss the point. Nature, as we observe it, is not nature-in-itself. My philosophy introduces the distinction between phenomena—the world as it appears to us—and the noumenon, the unknowable reality beyond our senses. Mathematics describes phenomena beautifully, but it cannot touch the noumenon.

Euler: (frowning) So, Kant, you would limit us? You say we cannot know the world as it truly is? What, then, is the purpose of reason?

Kant: Not to limit, Herr Euler, but to liberate. By understanding the boundaries of reason, we avoid chasing illusions. Mathematics, science, and art all enrich human experience, but they do so within the structures of the mind. This is no defeat—it is the foundation of the Enlightenment itself.

Goethe: (nodding) I find comfort in your words, Kant. Science must indeed be grounded in experience, but it must also embrace the human spirit. Knowledge is not merely what we measure, but what we feel, what we create.

Lagrange: (stroking his chin) And yet, we must also strive for universality. The laws of motion, the structure of equations—these reflect a harmony that transcends human limitations. Is it not possible that in mathematics, we glimpse the noumenon itself?

Kant: (smiling) Perhaps, Herr Lagrange. Or perhaps mathematics is the finest illusion of all. Either way, our task is clear: to continue the Enlightenment’s quest to unite reason, nature, and humanity. To knowledge, gentlemen.

Euler, Lagrange, Goethe: (raising their glasses) To knowledge!

(The fire crackles as the discussion deepens, each man contributing to the tapestry of thought that defines their era.)

Appendix: Kant, Euler, Lagrange, and Goethe

17th Century: Foundations of the Enlightenment

1642:

- Isaac Newton is born. His work in mechanics and optics sets the stage for later discussions on natural laws and the limits of reason.

18th Century: The Lives and Works of Kant, Euler, Lagrange, and Goethe

1707:

- Leonhard Euler is born in Basel, Switzerland. He becomes one of the most prolific mathematicians in history.

1724:

- Immanuel Kant is born in Königsberg, Prussia. He grows into a philosopher who revolutionizes epistemology and metaphysics.

1736:

- Joseph-Louis Lagrange is born in Turin, Kingdom of Sardinia. He becomes a mathematician and physicist known for his work in mechanics.

1749:

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is born in Frankfurt, Germany. He becomes a polymath known for his contributions to literature, natural science, and philosophy.

Mid-18th Century: Major Early Works

1744:

- Euler publishes Methodus Inveniendi Lineas Curvas (A Method for Finding Curved Lines), laying the foundations of variational calculus.

1755:

- Kant publishes A General Natural History of the Heavens, proposing a nebular hypothesis for the formation of the solar system.

1766:

- Euler publishes Institutiones Calculi Integralis, advancing integral calculus.

Late 18th Century: The Height of Their Careers

1781:

- Kant publishes the Critique of Pure Reason, introducing his revolutionary ideas about the limits of human knowledge, phenomena, and noumena.

1785:

- Goethe begins work on Theory of Colors, challenging Newtonian optics and proposing a more subjective view of light and color.

1788:

- Kant publishes the Critique of Practical Reason, focusing on moral philosophy and the role of free will.

1788:

- Lagrange publishes Mécanique Analytique (Analytical Mechanics), reformulating Newtonian mechanics in terms of energy and action, emphasizing general principles over geometry.

19th Century: Late Works and Legacy

1810:

- Goethe publishes Theory of Colors, presenting his theories on light and perception, which challenge Newton’s more mechanistic approach.

1833:

- Lagrange dies, leaving a legacy as one of the most influential figures in mechanics and calculus.

1832:

- Goethe dies, remembered as one of the most important figures of German literature and a pioneering naturalist.

Summary of Major Works by Each Figure

- Immanuel Kant (1724–1804):

- Critique of Pure Reason (1781): Examines the limits of human understanding and introduces the concepts of phenomena and noumena.

- Critique of Practical Reason (1788): Develops his moral philosophy based on reason and the categorical imperative.

- Critique of Judgment (1790): Bridges aesthetics and teleology.

- Leonhard Euler (1707–1783):

- Institutiones Calculi Differentialis (1755): Advances differential calculus.

- Institutiones Calculi Integralis (1768–1770): Develops integral calculus.

- Contributions to mechanics, fluid dynamics, astronomy, and number theory.

- Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1736–1813):

- Mécanique Analytique (1788): Reformulates mechanics using energy principles.

- Contributions to variational calculus, celestial mechanics, and the theory of equations.

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832):

- Theory of Colors (1810): Proposes a subjective view of color perception.

- Faust (Part I: 1808, Part II: 1832): A monumental work in literature exploring themes of human striving and knowledge.

- Contributions to natural history, including studies in plant morphology and geology.

[…] Modern Self Café v2: Kant Goethe There → […]